On Saturday 20th May, Dada Saheb Phalke’s film “Raja Harishchandra” was screened at the British Film Institute. But it wasn’t an ordinary screening. The silent film was screened with live music and a presentation about the early years of Indian cinema.

The brain behind the show was Lalit Mohan Joshi of SACF (South Asian Cinema Foundation) and it was executed with the help of his team which included his wife Kusum and daughter Uttara . The music was composed and conducted by Pandit Vishwa Prakash.

This film was made 104 years ago and is the first feature film made in India. Dada Saheb Phalke had been an assistant to Raja Ravi Varma in running his printing business. So he happened to be invited to the first screening of a film when the Lumiere Brothers came to Bombay with their new invention. He was totally fascinated by this new way of telling a story. He soon set up business himself.

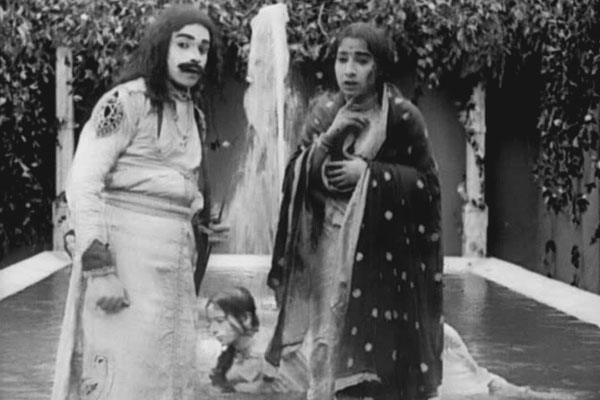

The copy which was screened at the BFI was only 20 minutes long but this is all that remains of the 40 minutes which was the original length. We know that most of the early films were sold and recycled to get the silver out of the celluloid and there are many famous films which are lost forever. The most remarkable thing about this film is that all the female characters are played by men. I had read about it many times but when I actually saw the scenes I couldn’t believe that the demure queen Taramati, sadly wiping her tears with the end of her sari, was actually a man! Apparently no women wanted to act in films in those days because they felt it was something shameless to be seen by everyone. The man who played the role of the queen was a cook in a small restaurant.

Pandit Vishwa Prakash must be given the credit for bringing to life this silent story. He not only composed the background music of the scenes but also the dialogues, some of which were sung and some were spoken. Among the very able singers was Pandit Vishwa Prakash himself for the male voices, while the mother-daughter duo, Uttara Sukanya Joshi and Kusum Pant Joshi, sang for the female roles.

The musicians who accompanied them were Surmeet Singh on the sitar, Avatar Singh Namdhari on the dilruba and Mitel Purohit on the tabla. It was the harmony among them that created the beauty of their music. The dilruba (also known as esraj) gave the strains like the human voice which touched the heart and brought out the pathos of some of the scenes. The point to note is that the music, the singing and dialogue were all done as the film was playing and they took their cues from the visuals. It had to be perfectly synchronised.

So, what was I doing there? Well, Lalit Mohan Joshi had the idea of having two women selling tea and paan/bidi to the music composer, just as they would have done a century ago in a little cinema hall in Bombay. I along with a volunteer Charu Smita enacted that scene before the musicians sat down to play in front of the screen.

The second session which took place after a break of an hour was equally enthralling. In answer to Lalit Mohan Joshi’s questions Pandit Vishwa Prakash recounted some very interesting and unknown anecdotes about the music of the early decades of the Indian cinema. There were relevant clips from the films he spoke about bringing before the audience scenes that they would not get to see easily. Pandit Vishwa Prakash also sang bits of the songs to illustrate a point. The show ended with a song from the film “Guide” sung marvellously by Uttara Sukanya Joshi.